- Eternal Recurrence

- Posts

- Tom Stoppard, my real thing

Tom Stoppard, my real thing

"Since we cannot hope for order, let us withdraw with style from the chaos."

I can’t recall the last time the death of a public figure felt like such a personal loss, but so it has been with the death last week of Tom Stoppard. As I watched the love pour forth, I had that strange sensation of an admired artist that I absurdly believed was somehow uniquely mine; only to be reminded he had, of course, been beloved by many. This as it should be. He was one of the giants of his age.

But he was also a titanic influence on me. Intellectually, culturally, creatively. From the moment I saw The Real Thing on Broadway as a 20-year-old, Sir Tom was something of a literary lodestar, and I would travel the world to see his work. Though he was raised in England, he was born in Czechoslovakia, and he never shed that strange Mitteleuropean essence that felt so familiar, no, familial, to me.

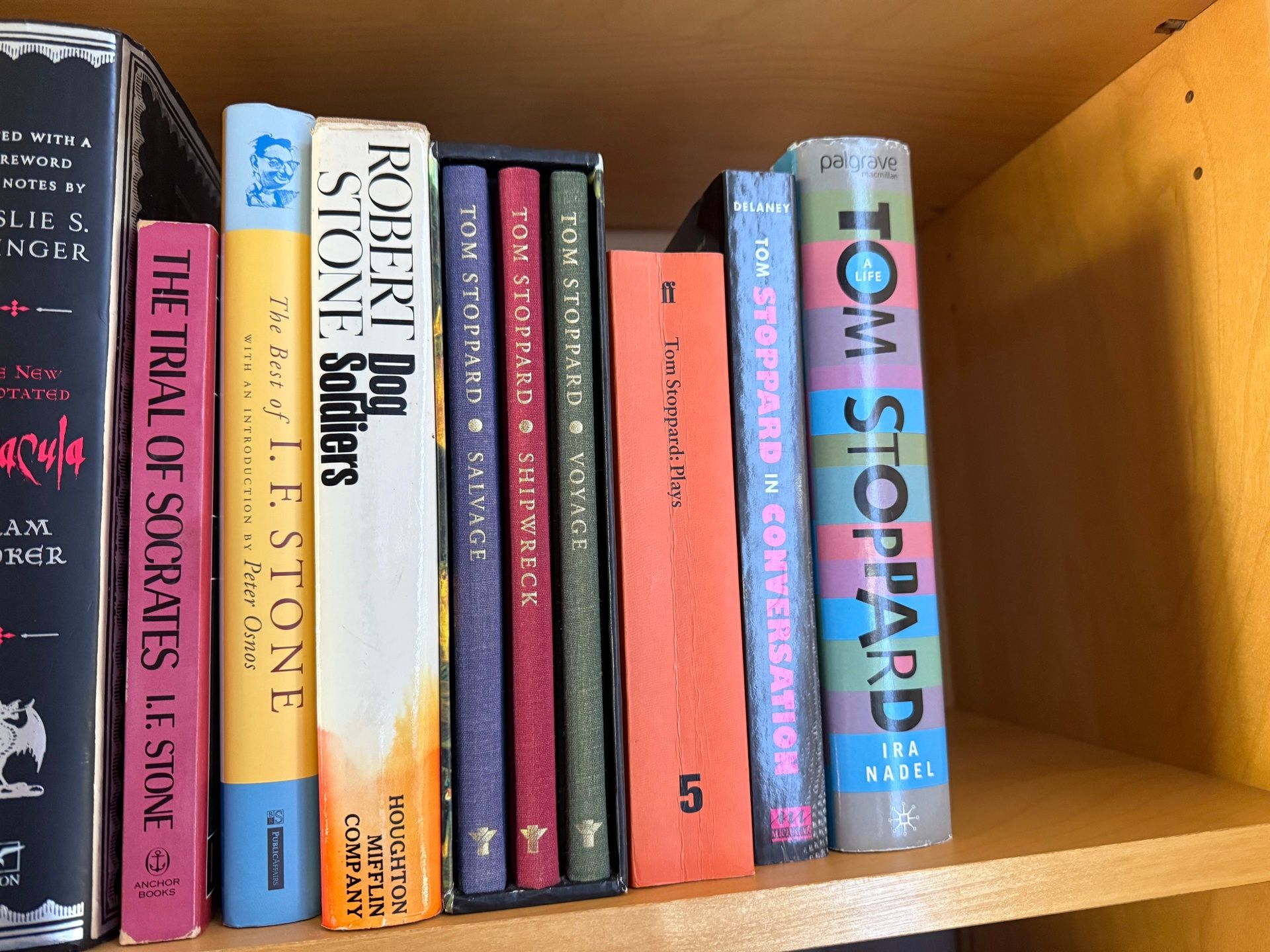

Shelf one, missing the Lee bio and the Cambridge Companion, on my desk as I write.

I was traveling with the kid when the news of his passing broke, away from my trusty library. Since I got back, I have been revisiting his work, which spans a couple of shelves in my library. What follows is not a critical or biographical appraisal - there are plenty of those to go around - but rather smattering of Stoppard memories from the last forty years.

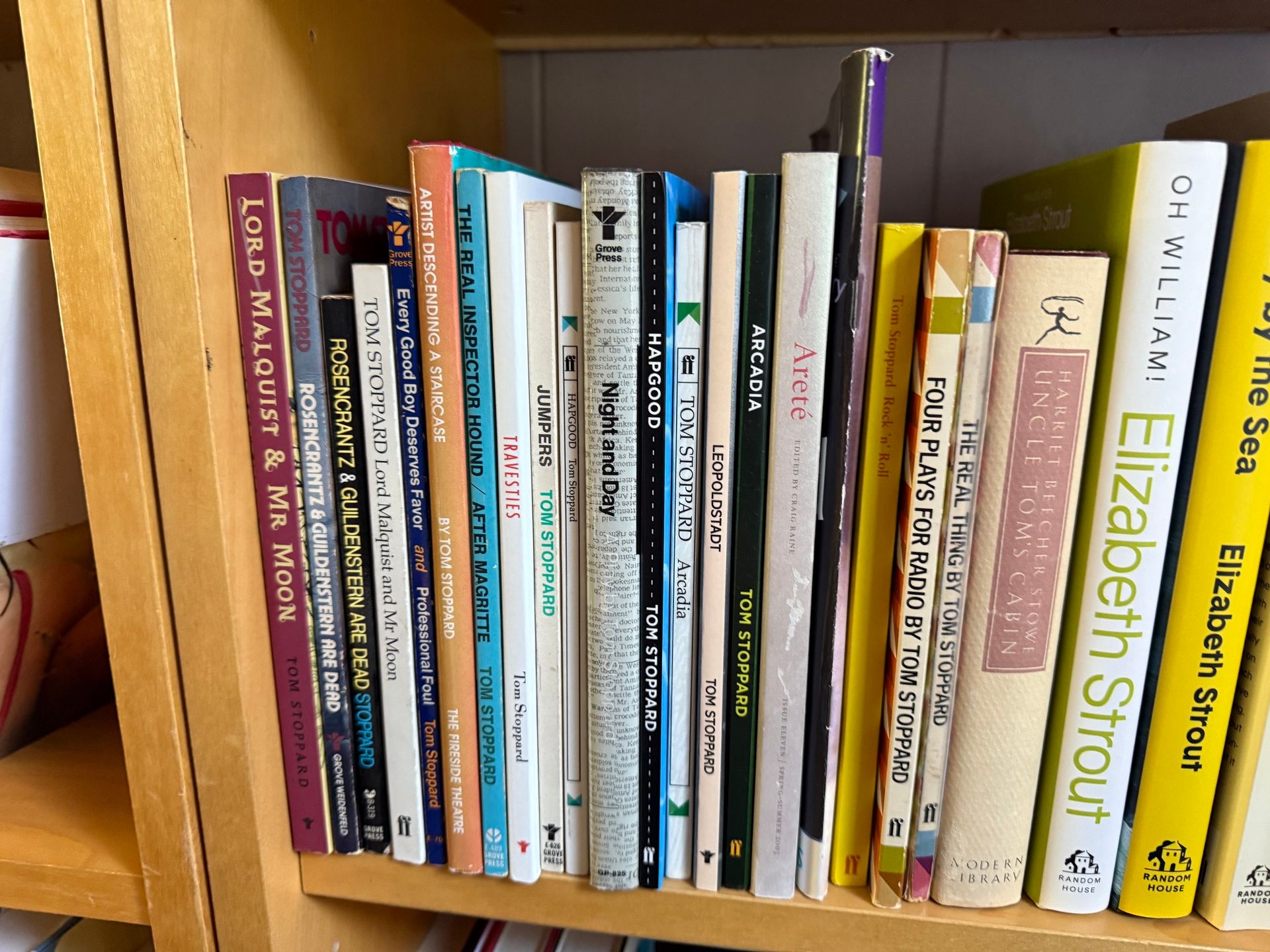

Shelf Two, minus Invention of Love, also on my desk.

// 1984

I was lucky enough to see The Real Thing with its original cast, Jeremy Irons, Glenn Close, and from that moment I was gone. I bought the LP and the published play, and listened and read endlessly, committing whole chunks to memory. I had a part-time “job” in college, delivering airplane tickets (remember those?) to customers of my mother’s travel agency. I would walk for miles through Manhattan muttering the speeches to myself, lost in the splendid music of Stoppard’s dialogue. (I went back to New York in 2000 to see the Donmar Warehouse revival with Stephan Dillane and Jennifer Ehle. I found him too broad, too much mugging. But she was luminous and supplanted Close in my mind’s eye staging.)

As it happened, at this time I was an editor of the NYU student newspaper and a co-editor of its art supplement. Under those auspices, I wrote Stoppard a long and fawning letter about the play, which I deemed to be the truest yet written on the topic of love, and requesting an interview. Imagine my surprise when some weeks later, I received a personal note card from Stoppard, inviting me to mail him interview questions. (I hoped to locate this note to include a picture here; but that would require hours of garage digging, so I’ll just tell you it was a small embossed 3×5 white notecard that said TOM STOPPARD, IVER BUCKS across the top. It was hand typed and signed in fountain pen.)

What followed was a colossal and uncharacteristic failure of nerve.

I wrote about a dozen questions, had them all set to go. And I re-read them and even my unformed twenty-year-old self realized how fucking banal and lame they were. And so I never replied, and to this day, friends refer to it as the best interview I never wrote.

You needn’t ask. Of course I regret it.

(A coda from 2008. I was invited to the Texas Book Festival when my first novel came out. All the visiting writers were treated to a guided tour of the Harry Ransom Center, the great archive at the University of Texas Austin. The docent advised that they had recently acquired and catalogued Tom Stoppard’s papers. I mentioned my 1984 missive and idly wondered if it was in the stacks. “Let’s have a look,” he said, and moments later I was holding my original letter. Here’s the catalog listing:)

You will have to submit a research request if you want to read it …

//1990

By this time I was living in Los Angeles, and the Brentano’s in Century City (lovely spot, long gone), announced that Stoppard would be signing copies of the film tie-in edition of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. (I still remember his wonderful remark about why he agreed to direct the film. “I am the only one who would show the source material the necessary disrespect.”)

By that time, I had a growing collection of his plays, as seen above, so I hauled them all out, and he graciously signed each one. He paused to peruse my hardcover copy of his 1979 play Night and Day, raised an eyebrow and said, “Even I don’t have this one.” I considered offering it to him on the spot but he signed it quickly and handed it back. I found his charisma dizzying, and stumbled home happily with my haul.

“Even I don’t have this one.”

//1997

When The Invention of Love came to Broadway, I was lucky enough to snag a pair of house seats thanks to an actor friend of mine who had been in a film with Daniel Davis, who was now playing Oscar Wilde as part of the original cast. I brought along my mother as my plus-one, who loved Stoppard, but perhaps more importantly, loved the sitcom The Nanny, in which Davis played the long-suffering butler. We were invited backstage to say hello to him afterwards. He was lovely, gracious, welcoming, and my mother was charmingly tongue tied and starstruck, burbling about The Nanny, much more impressed by the TV credential. Still, it’s something she talks about to this day. And Davis’s magnificent closing speech as Wilde - “Better a fallen rocket than never a burst of light” — lives in my memory to this day.

//2002

The moment The Coast of Utopia went on sale at the National Theatre, I bought tickets - theatre and plane - and saw all three plays over two days. I knew enough to do my homework going in; I read Herzen’s My Past and Thoughts, Berlin’s Russian Thinkers, and Carr’s The Romantic Exiles, all of which Stoppard has cited as research sources.

I was jet-lagged, overloaded, but I like to think I kept up. My favorite memory of this visit came during the intermission of the second play, when an older British gentleman sitting a few rows in front of me turned to me and asked with exquisite diffidence, “Do you … understand what is going on?”

I did my best, shared what I could. I like to think it helped him a little.

//2007

During the height of my Elegant Variation days, Grove Press saw fit to reissue Stoppard’s only novel, Lord Malquist and Mr. Moon. (The quotation about withdrawing from chaos above is drawn from the novel.) I wrote an essay about it for the Threepenny Review that remains my favorite piece of criticism I’ve written. Though I was rather hard on the novel, I thought it was a fascinating bellwether for the themes that would pursue Stoppard through his playwriting career. I also used it as a chance to write about Arcadia, which I consider his masterpiece. (When the new Old Vic revival was announced a few weeks back, I immediately bought tickets for February, having only seen the original production — Rufus Sewell! — and a dreadful Pasadena Playhouse production. Traveling to see Stoppard has clearly long been a thing; I blew off a few days of a Bennington MFA residency to run into New York to see Tom Hollander’s 2018 revival of Travesties.)

You can read the review here. I really am quite proud of it.

My original Septimus. Rawr.

//

I save my most controversial Stoppard take for last. (No, it’s not about Leopoldstadt, though it’s true I did not esteem it as highly as others, yet I was perfectly delighted to see him collect what I suspected would be his final Tony.)

No, I close with a full-throated, unshakeable defense of the unfairly maligned Shakespeare In Love. I remember seeing this with friends on a Sunday morning at the AMC in Century City, and when it was over we stumbled, red-eyed and speechless, into the morning. Even over lunch, the spell was on us, we could barely find the words for what we’d just seen. I think it’s fucking magnificent, near-perfect, an absolute gift to anyone who loves the theatre. I’ve never really understood the anger directed toward it - people seemed alternately hung up on Gwyneth’s accent or the perceived Spielberg snub, I don’t know. (And what a slog Saving Private Ryan was, bloated and sentimental at once.)

But it is a movie full of delights, and a script brimming with easter eggs for any lover of Shakespeare, of the theatre, of writing. It’s richly intelligent, witty as hell, and restores Romeo and Juliet from that stale, oft-quoted staple of high school English to a living tragedy. If you really do hate this glorious movie, perhaps there is some defect in your heart. Stoppard’s Oscar was richly deserved. Get yourself checked out.

I know I could go on. But there are plenty of tributes out there demanding your time. I especially recommend these recent articles:

A lovely insider’s remembrance.

This appreciation in The New Yorker.

His Guardian obituary.

Essays like these customarily end with some formulation to the effect of the world being a poorer place without the presence of the subject in question. I always sort of nod as those words drift over me. On the one hand, all voices sooner or later are stilled. On the other, for me at least, I confess to finding the world without Tom Stoppard’s radiant mind and voice to be a considerably colder and less inviting place. It’s surprisingly hard to get my head around his absence. I guess I have the rest of my life to try. In the meantime, I leave you with these words from Arcadia:

“The ordinary-sized stuff which is our lives, the things people write poetry about—clouds—daffodils—waterfalls—what happens in a cup of coffee when the cream goes in—these things are full of mystery, as mysterious to us as the heavens were to the Greeks.”

P.S. I suppose I must mention here, briefly and in passing, that my 2026 Writing Retreat is now open for registration. Warm holidays wishes to all of you.